Reduce Art Flights

About RAF

RAF / Reduce Art Flights is a campaign which upholds that the art world—artists, curators, critics, gallerists, collectors, museum directors, etc.—could or should diminish its use of aeroplanes. It was initiated by the artist Gustav Metzger (10 April 1926, Nuremberg—1 March 2017, London). [1]

This website (first established in 2008 and originally at reduceartflights.com) is maintained by the curatorial office Latitudes as a resource for the initiative and as a location for future elaborations of its aims.

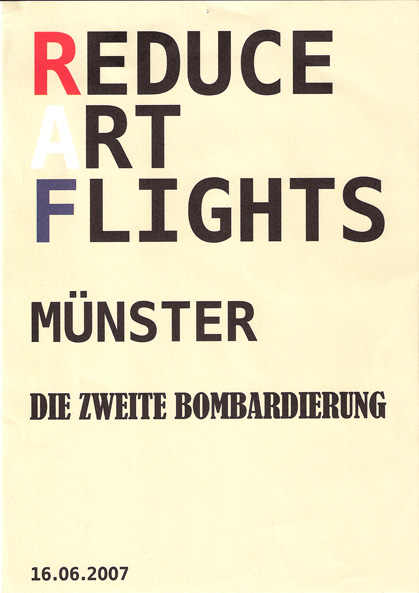

The RAF acronym deliberately echoes the Royal Air Force—the aerial warfare branch of the British military—as well as the militant left-wing group known as the Red Army Faction. The campaign had been mooted by Metzger for a year or so, before being realized as a mass-produced leaflet on the occasion of the artist’s participation in ‘Skulptur Projekte Münster 07’ (Sculpture Projects Muenster 07) in 2007. The design of the 5,000 leaflets was based on a 1942 Royal Air Force poster that detailed the aerial bombardment of Germany during the Second World War. The project conjoins the historical memory of airborne destruction (Münster was among several cities devastated by air-raids), with Metzger’s “ongoing and endless opposition to capitalism”, and his “objection to the massive commercial growth of the art industry”, exemplified by the unprecedented art tourism of the 2007 “Grand Tour” (the coincidence of the 52nd Venice Biennial; the five-yearly Documenta 12, Kassel; and the once-a-decade Sculpture Projects Muenster itself). [2]

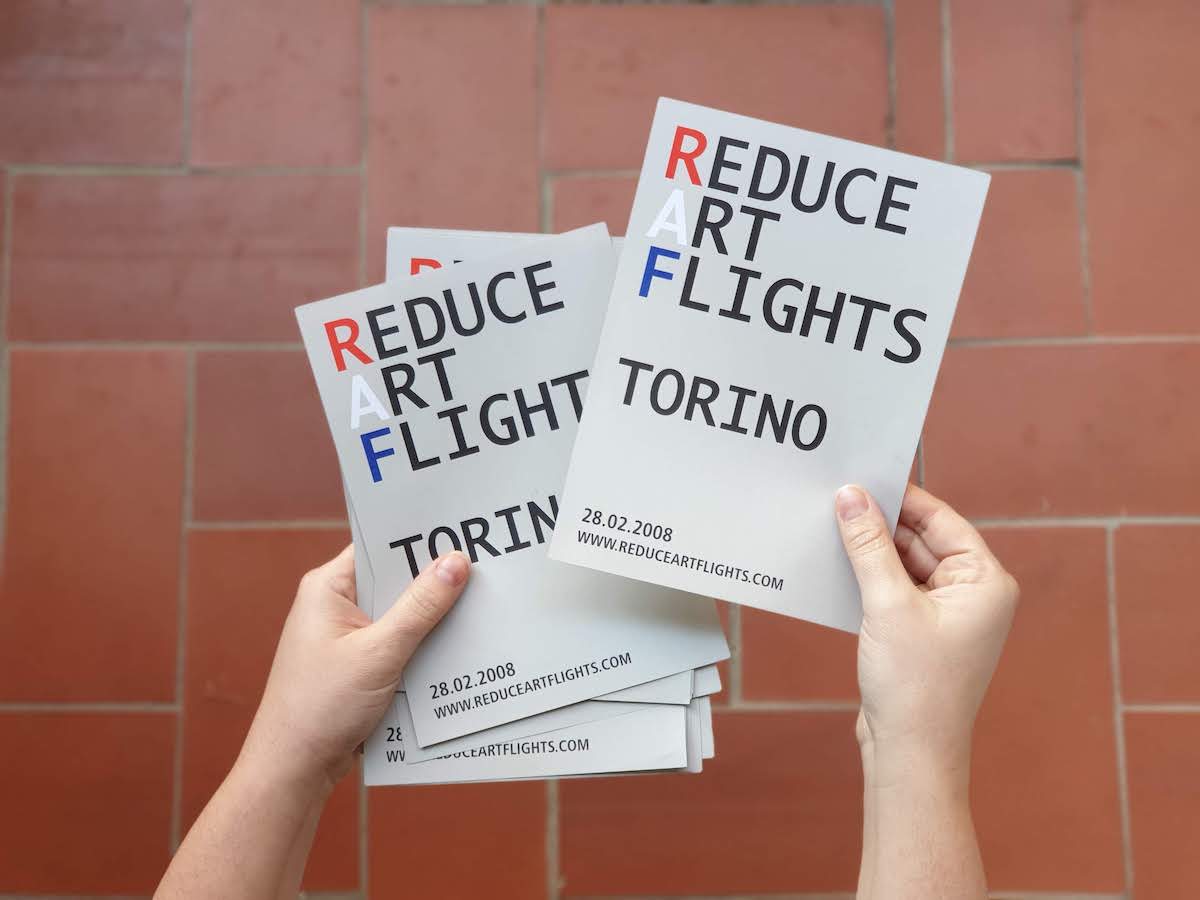

The RAF initiative is neither a work of art, nor an idea over which Metzger claimed ownership or leadership. This website (and this text) grew out of the reactivation of the RAF initiative as part of the exhibition ‘Greenwashing. Environment, Perils, Promises and Perplexities’ (Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, Italy, 29 February—18 May 2008). On this occasion the curators Latitudes and Ilaria Bonacossa) were guided by the artist’s advice concerning how the campaign could be extended. RAF Torino consisted of the printing of a new version of the leaflet, made available in the galleries and inserted into international mailings in connection with the exhibition, and the distribution and attempted implementation of its inherent request to “consider forms of travel and transportation other than flying” in the process of the organisation of ‘Greenwashing’. [3]

Leafleting is one of the most elementary forms of campaigning and propaganda. Somewhat ironically in this context, among its most effective applications in the last century has been through the deployment of aeroplanes to drop leaflets as a form of psychological warfare. The plea to reduce art flights—however viable or compelling it may be—does not attempt to address practical means to alleviate art world aviation itself. Instead, Metzger suggested the “reduce, reuse, recycle” mantra of environmentalism be transformed and integrated into a more radical spectrum of consideration of humanity’s destructive potential. With full cognisance that it is “a drop in the ocean”, the RAF manifesto nevertheless invites voluntary abandonment—a fundamental, personal, bodily rejection of technological instrumentalization and a vehement refusal to participate in the mobility increasingly endemic to the globalized art system. [4]

Text by Max Andrews [5]

- “At last year’s Art Basel I felt that something should or could be done in relation to the flights, both of artists and gallery people, and the transportation of works of art.” Gustav Metzger quoted in Mark Godfrey, “Protest and Survive”, ‘Frieze’, Issue 108, June–August 2007.

- Ibid.

- Gustav Metzger, telephone conversation with Max Andrews, 1 November 2007.

- Gustav Metzger quoted in Mark Godfrey, op. cit.

- This text is based on a version first published in the exhibition catalogue ‘Greenwashing. Environment: Perils, Promises and Perplexities’, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, edited by Latitudes & Ilaria Bonacossa, published by the The Bookmakers Ed., Turin, 2008, ISBN: 978-88-95702-01-8.

Interview

Gustav Metzger interviewed by Emma Ridgway, 13 February 2008, London (12' 56")

- Transcript

Gustav Metzger: The RAF project is an attempt to link different aspects of the art world to the real world, and of course RAF is a summing up of the idea of reducing art flights. So Reduce Art Flights = RAF. But of course RAF stands for Royal Air Force and there we think back on the last war, World War II, and RAF Royal Air Force played such a decisive part in that war and the victory over our enemies. And so it’s linking this up with the past war and the danger of war, but it also links up with something more up-to-date which is RAF in German, which stands for Rote Armee Fraktion. That was the guerrilla movement in Germany, particularly in the 70s, where the RAF, the so-called revolutionaries, tried to seriously damage the German political and economic life. And so this was interesting to me, that RAF stand for a multiplicity of historical realities and present-day issues such as the danger through pollution, and in this case the danger of pollution from aeroplanes — and of course there is also noise pollution from airplanes. Specifically it was brought together in connection with the Basel Art Fair of 2006, when I rang a few friends in Basel. So I rang a few people in Basel, some of them I knew, and asked if they could distribute this idea, Reduce Art Flights RAF, and the answer was that it was just too short a notice. So this never happened in Basel, this protest, this attempt to influence the art world to travel less or not to travel at all, and not to ship artworks through the skies.

Then there came the invitation to exhibit with the Münster Skulptur Projekte, which I accepted, and I travelled there. Before travelling I was given the catalogue of the previous Münster Skulptur Projekte exhibition. In that catalogue there was a short sentence which had a big impact on me, that said that the bombing of Münster (Münster was heavily bombed in the last war) was in a retaliation for the German wholesale bombing of Coventry in 1940. That sparked off the idea that I could somehow or other commemorate these two bombings campaigns as my contribution to Münster. Eventually that’s what happened after I had visited Münster for a kind of investigation. While this happened, talking to the director of the Münster Kunstverein who was also active as a curator for the Munster Skulptur Projekte, the idea came up again of RAF, since it was the RAF that actually bombed Münster (the RAF and American planes) – to, as it were, revitalise this Reduce Art Flights. This is what happened, the idea was accepted and by the time the show opened some months later some very nicely print leaflets were available to the visitors and the leaflets said “RAF”, “Reduce Art Flights”, and then in German “Münster”, “Die Zweite Bombardierung”, which means the second bombardment of Münster. There again it was a treble meaning, the bombardment of Münster through the present-day aeroplanes going across and putting pollution onto the town, and then again the second bombardment of Münster by my exhibition dealing with the past, and these leaflets, 5000 were printed, being distributed to all the visitors to the exhibition. So that in a nutshell brings this project together.

But it’s not ended, it goes on, it could go on for years because I don’t imagine the art world will give up using aeroplanes for transportation. But it’s a kind of... it’s a nudge in the ribs as it were to remind people there is a problem and let’s talk about this problem of endless flights here and there. What particularly annoyed me originally was the statement by the organisers of the Basel art fair that when it comes to take the fair to Miami, which was planned, everybody could get a 50% reduction on the aeroplane flight. I thought that is just over the top, pumping up the possibility of aeroplane use. So for me this has very much to do with a rejection of mass transport through air of course, and through cars and buses, and also a criticism of the art world where everything is out for maximizing everything and in every direction.

Emma Ridgway: Could you talk a little about your objections to the commercialisation and commercial activities in the art world. Does it relate to that?

GM: Yes, is it definitely related, it’s definitely linked to this issue. My rejection of the art gallery system goes back to the early 60s. It hasn’t actually weakened and when we now see these big and powerful art magazines like Artforum consisting mainly of advertisements for private galleries, I do get upset. At the same time one can’t resist the seduction. So much effort goes into making each page and of course vast amounts of money go in making these products. Fees have to be paid. Nonetheless I was in the library today and there is a certain appeal in the colour and invention. But in principle, I think it’s going the wrong way and it’s a massive escalation that we’ve seen it in every decade, there is more-and-more advertisements and more-and-more galleries and in a sense more power to the galleries. I am very upset by all of that.

ER: One thing that comes up from thinking about not taking flights within the art world, when it’s so international in how its activities operate right now, is one of speed versus slowness. I’m just wondering if you could talk about that?

GM: Well, speed is increased dominating life and of course the mobile telephones is a chief example of how everything is being speeding up. People now have and seem to want instant. They want to instantly speak to the person in China, or in the room next door. Often people use their mobile... don’t they, these days... or email, to call their wives to meet behind the next wall. I think all of that is really terrible, this principal of instantaneity. Life hasn’t been like that and it contradicts the kind of organic interchange that that people really could have and I think should have. Again it has to do with commerce: you have a chance to make a deal, let’s make the deal now. It’s all very, very sad.

ER: Do you have particular intentions and ideas of what people might do in receiving the message at RAF campaign?

GM: Quite frankly I am not optimistic about actually affecting people’s behaviour but I think people’s thinking... you know these little printed pieces of paper, can have a certain impact on the way people think. Of course people will relate it to the vast attention given to so-called climate change and environmental dangers, and I think you’ve noticed that more and more artists are engaging with these issues. There’s no question, in this country, in Great Britain certainly, it’s almost a daily increase in awareness in the art community of problems that are dealt with on a world scale by governments, or think tanks, or scientists. I think that’s rather good. In that wider movement towards a kind of involvement with political, economic and world issues, this little contribution can play its part, I would expect it will. Of course the more of these pamphlets... that we had in Münster and are now going to have in Turin... the more places this idea turns up in the better. I think it will go on from place to place being distributed and being considered by the art world.

ER: Wonderful, huge thanks Gustav.

Exhibition History

For any omissions or clarifications, please contact us at the following email, and kindly send a copy of your campaigns to help complete this archival resource:

For questions regarding the implementation of future campaigns, please contact The Gustav Metzger Foundation:

‘skulptur projekte münster 07’ [sculpture projects muenster 07]

LWL-Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Münster, and public space in the city

17 June–30 September 2007

‘GREENWASHING. Ambiente: Pericoli, Promesse e perplessità’ [Greenwashing. Environment: Perils, Promisses and Perplexities’

Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Torino

28 February–18 May 2008

‘World Portable Gallery Convention 2012’

Eyelevel Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia

5–8 September 2012

‘Gustav Metzger – Years without Art’

Morat-Institut für Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

13 April–15 June 2013

‘Debemos convertirnos en idealistas o morir. Gustav Metzger’ [We Must Become Idealists or Die]

Fundación Jumex, Mexico City

19 July–25 October 2015

“Actuar o perecer. Gustav Metzger – Una retrospectiva” [Act or Perish. Gustav Metzger – A Retrospective]

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de CastIlla y León, León

17 September 2016– 8 January 2017

‘Gustav Metzger. Remember Nature’

Musée d’art moderne et d’art contemporain (Mamac), Nice

11 February–14 May 2017

‘Gustav Metzger. Oeuvres sur papier’

CIRCUIT, Centre d’art contemporain, Lausanne

2 September–1 December 2018

(leaflets 28.09.2018 and 02.11.2018)

Collection Display: Gustav Metzger

Artist and Society, Room 7

Tate Modern, London

1 February 2022–28 April 2023

Gustav Metzger. And Then Came the Environment

Hauser & Wirth, Downtown Los Angeles

13 September 2024–12 January 2025

Bibliography (selected)

- Mark Godfrey, “Protest and Survive”, frieze, Issue 108, June-August 2007.

- Latitudes & Ilaria Bonacossa, eds., “Greenwashing. Environment: Perils, Promises and Perplexities”, exhibition catalogue, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin / The Bookmakers Ed., 2008.

- “Greenwashing update: RAF / Reduce Art Flights. Gustav Metzger interview”, Latitudes blog post, 6 March 2008.

- Eva Scharrer, “Greenwashing”, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Artforum, Summer 2008.

- “Gustav Metzger's RAF / Reduce Art Flights campaign initiative changes URL to www.reduceartflights.lttds.org”, Latitudes blog post, 28 January 2009.

- “Vanishing Point. Gustav Metzger & Self-Cancellation: Round Table Discussion, Chair Brian Morton”, Mackintosh Room, Glasgow School of Art, 16 February 2008. Part of Instal08 Festival, The Arches, 14-17 February 2008.

- Sophie O'Brien and Melissa Larner, eds., “Gustav Metzger: decades, 1959-2009”, Serpentine Gallery / Koenig Books, 2009.

- “Reduce Art Flights leafleting campaign by Gustav Metzger at the Serpentine Gallery, London”, Latitudes blog post, 21 October 2009.

- Ruth Catlow, “We won't fly for art: Media Art Ecologies”, in “Paying Attention: Towards a Critique of the Attention Economy”, Culture Machine, vol 13, 2012.

- Emma Ridgway, “RAF” (composite from three interviews with Gustav Metzger, 2008-12), in “World Portable Gallery Convention 2012”, exhibition catalogue, Eyelevel gallery, Halifax, pp. 35-50.

- Kirsten J Swenson, ‘Critical Landscapes: Art, Space, Politics’, University of California Press, 2015, p. 213.

- Raimar Stange, “Weathermen”, Flash Art, 16 December 2016.

- Elizabeth Fisher, “Gustav Metzger (1926–2017)”, Apollo, 6 March 2017.

- Hélène Guenin, “Gustav Metzger Act or perish”, switchonpaper.com, 19 July 2018.

- Claire Bishop and Nikki Columbus, “Free Your Mind”, n+1 magazine, 7 January 2020.

- CIMAM – International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art, “Toolkit on Environmental Sustainability in the Museum Practice” (see “Inspiring Projects, Platforms, and Resources”), 6 July 2021.

- Max Andrews, “Reduce Art Flights. Gustav Metzger” in “Arts of Coming Down to Earth. Cultural institutions and ecological emergency: how to land on terrestrial futures?”, Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro (Ed.), Taipei Biennial 2020, Bamboo Curtain Studio and Taipei Fine Arts Museum, November 2020, pp. 33–34.

- Nicholas Ferguson, “After flight. Visions from London Heathrow”, ‘Futures’, Volume 153, October 2023.

- Max Andrews, “Frequent Flyers: Robert Smithson's ‘Aerial Art’ (1969)”, Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Text Program Chapter 7, October 2024. ISBN 978-1-952603-36-5

- John-Paul Stonard, “Why seeing art by train should be the next big thing”, The Art Newspaper, 17 January 2025.